Pagan Magic of the Northern Tradition: Customs, Rites, and Ceremonies - Nigel Pennick 2015

Keeping Up the Day

MARK DAYS AND TIMES OF THE YEAR

Traditional festivals held on specific days are often called Calendar Customs, but in actuality they are related to the time of year; the calendar only marks their place in the year. They celebrate either important days in the annual day-length cycle, the changing of the seasons, or religious festivals, many of which relate to the particular season. Aspects or fragments of various old traditions are incorporated in certain festivals: Some are initially pre-Christian in origin, such as Yuletide and May Day; some are derived from Roman Catholicism, such as the holy days of St. Valentine’s and St. George’s Day. Some are national festivals with a political origin, such as various Independence Days, National Days, Guy Fawkes’ Night, and Remembrance Sunday. Some are to do with the annual cycle of agriculture, such as the harvest. Others are festivals of local veneration of official or unofficial saints. They have countless local customs connected with them all over northern Europe, and a few characteristic ones are detailed here. The very diversity of origins and syncretic practices of the year cycle make it futile to assign these mark days to a particular religion, sect, or nation.

They have reached their present state through many changes and additions, and they continue to evolve as new people find new ways of interpreting them. Each individual performance will differ in some way from the previous one, and from others happening in other places at the same time, yet to “keep up the day” in whatever relevant way is to carry on the tradition. Some festivities that continue in the twenty-first century owe their survival to local societies who kept them going against official opposition. In Scotland, lodges of trade guilds such as the Horsemen’s Society and the Oddfellows preserved the old forms of festivity when they were dying out from universal observance. This is one of the functions of traditional unadvertised groups in “keeping up the day,” making their appearances only during their rites and ceremonies of the appropriate day, whether they are expected or not.

WAYS TO DEFINE THE YEAR

The solar year can be defined in four different traditional ways: the vegetation year, the flower year, the harvest year, and the maritime year. There are ten possible year cycles:

Solstitial solar years: |

December—June—December; |

June—December—June |

|

Equinoctial solar years: |

September—March—September; |

March—September—March |

|

Vegetation Years: |

November—May—November |

Flower Years: |

May—November—May |

Harvest Years: |

August—February—August; |

February—August—February |

|

The Maritime Year: |

April—October—January—April; |

October—January—April—October |

Between the two solstices, the traditional rural calendar in Britain and Ireland marked the end and beginning of winter by the festivals of May Day (Beltane) and All Saints’ (Samhain), respectively May 1 and November 1 in the modern calendar. In medieval times the agricultural year was regulated by the church’s “red letter days,” particular saints’ days that either continued pre-Christian practice or coincided with it. Practically, these days were only an indication, as the fluctuations in the weather that might lead to an early or late harvest, for instance, were the real events that mattered.

THE ANGLO-SAXON YEAR

In the north the physical fact of long days in the summer and short days in the winter is the common feature of the traditional observances. The different ways of life—pastoral, agricultural, industrial, mercantile, and military—all have their contribution to make to days that mark the passing of the years. In England the ancient year-cycle is known in detail. The fervent faith of the early Christian missionaries drove them to obliterate local ancestral traditions and impose the new religion on them instead. Although early Christian chroniclers hated the traditional rites and ceremonies of the country people around them, in their attempts to discredit the elder faith, they wrote about them, in horror. Fortunately, they recorded what our spiritual ancestors did, and because of this, we can understand the meaning of their rites and ceremonies.

The seventh-century chronicler Bede tells us that the ancient Angles divided the year into two halves, defined by the solstices. Each solstice was bracketed by a preceding and following month. In the winter there was Ǽrra Geóla, “Before Yule,” the month before the winter solstice, and Ǽftera Geóla, “After Yule,” the month after it. Similarly, in the summer time, two months bracket the summer solstice: Ǽrra Líða before Midsummer, and Ǽftera Líða after it. The Anglo-Saxon months had names descriptive of their qualities. January was Ǽftera Geóla; February was Sol-mónaþ, “Mud Month” (later called “February fill dyke”); and April Eóstre-mónaþ, which was the first month of spring. Eostre was the Anglo-Saxon goddess of the dawn and of springtime, and she gives her name to the festival of Easter, though its actual date is reckoned according to a modified version of the ancient Jewish calculation of Passover. May was called Þrí-milce, “Three Milkings,” an abundant time when cows have plenty of milk. Ǽrra Líða, “Before the Summer Solstice,” was equivalent to June; July was Ǽftera Líða. August was Weód-mónaþ, “Weed Month,” and September Háligmónaþ, “Holy Month,” the month in which the harvest festival was celebrated. The church banned the name Hálig-mónaþ and the new month-name Hærfest-monaþ, “Harvest Month,” was invented. October was Winterfulleþ, the month that began winter. November was Blótmónaþ, “Sacrifice Month,” when slaughtered animals were dedicated to the gods. Finally, December, the month before Yule, was Ǽrra Geóla.

YULE

Throughout northern Europe, religious festivals are linked with the seasons, and related folk customs reflect the character of the time of year when they are performed. In the north, winter darkness is more protracted than farther south, and the midwinter solstice, celebrating the return of the light after the longest night of the year, is the major festival of the year. Celebrated with feasting and fires, disguise and games, it is the Old Norse Yule, the “yoke of the year,” December 21, the shortest day. This festival was celebrated all over northern Europe, and Christmas is its continuation. It was the Norse Jul, Slavic Kračun, and the Lithuanian Kūčios and Kalėdos. The festivities of Yule went on for twelve days, the Twelve Days of Christmas, a time of respite from the hard labor of everyday toil.

YULETIDE GUISING

All over Europe, in the same way that the church sought to extirpate Pagan worship at an earlier period, repeated attempts were made to stamp out the unregulated festivals of the common people. The medieval church was especially ardent in its attempts to wipe out midwinter rites and ceremonies. Records of the attempted suppression of performance traditions, especially those involving animal and other disguises, give us some idea of the nature and content of these events. Clearly, the church suppressed performances when it could; the documentary record is fragmental, but repetitive. There was an especial hatred or fear of people wearing masks and putting on ritual animal disguise. One of the bynames of Odin is Grimnir, interpreted literally as “the one with the grimy (blackened) face,” or “the masked one.” Grime means frost or dirt, and a grim face is one frozen in a forbidding expression. The Old Germanic words isengrim, a mask covering the head, or egesgrîma, a “terrifying mask,” refer to this.

The continuity of masked guisers and those wearing ritual animal disguise is recorded in the history of their prohibition. In what is now Spain, the Bishop of Barcelona banned the stag play in 370 CE (Alford 1968, 122—23). There is a fourth-century calf mask (vetula) from Liechtenstein preserved in the Österreichisches Museum für Volkskunde in Vienna. In France in 543 CE, Bishop Caesarius of Arles attempted to suppress mum-ming in ritual animal disguise in the likeness of calves and other beasts (Bärtsch 1998 [1933], 34). Similarly, in 643 the Lombard king Rotharius ordered that those who wore a mask (masca) or a disguise impersonating dead warriors were to be punished. Around the same time, Bishop Eligius of Noyes (died 659) issued edicts against mumming. In 578 CE a church Council at Auxerre, Burgundy, forbade disguisings, and another Council, in the year 614, stated it was “unlawful to make any indecent plays upon the Kalends of January, according to the profane practices of the pagans.” In the ninth century Hincmar of Reims told his parishioners that “one must not allow reprehensible plays with the bear, nor with woman dancers, to be performed.” Hincmar used the word talamasca, also used by prohibitionists Regino of Prüm (ca. 900) and Burchard of Wurms in 1020. It appears that Christian missionaries to Pagan territory sometimes mistook the outings of guisers and mummers as an apparition of the Mesnée d’Hellequin. Ordericus Vitalis recorded in his Ecclesiastical History that in January 1091 a priest out in open country at Bonneval near Chartres in France came across the Wild Horde, led by a giant carrying a club followed by a horde of demons. This outing of the Mesnée d’Hellequin is the earliest known literary reference to the Harlequin disguise. The description tallies with contemporary demonic guisers who appear now around midwinter in events such as the Perchtenlauf (Perchten procession) of south Germany and Austria.

Saxo Grammaticus (ca. 1200) recorded the practice of setting the severed head of a sacrificed horse on a pole for magical purposes, and the horse appears as a major theme in ritual disguisings at midwinter (Saxo 1905, 209). In Iceland at the same time, between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries, successive bishops condemned people who sang ceremonial songs called Vikivakar, man-to-woman and woman-to-man. The performances involved animal disguise, the hestleikur (“horse game”), a man covered with red cloth guising as a horse (Alford 1968, 132). In twelfth-century England the Bishop of Salisbury, Thomas de Cobham (died 1313), condemned all kinds of actors, especially those who transformed their bodies by contortions and those who wore masks. In thirteenth-century England prominent clerics issued edicts attempting to suppress various practices. Around 1240 the Bishop of Lincoln, Robert Grosseteste, and the Bishop of Worcester, Walter de Chanteloup, both made “disciplinary pronouncements.” Chanteloup’s Constitutions (1240) and Grosseteste’s prohibitions (1236—1244) condemned most folk customs, including some of Christian origin. Among them were miracle plays, “scot-ales,” “ram-raisings,” and May Games and other athletic competitions, together with craftsmen’s “guild-ales” and the ceremonies of Festum Stultorum and the Inductio Mali sive Autumni. Around 1250 the University of Oxford authorities thought it necessary to forbid the routs of masked and garlanded students in the churches and open places of the city.

Fig. 16.1. Perchtenlauf at St. Johann, Pongau, Austria.

In the following centuries the Orders of the city of London for 1334, 1393, and 1405 forbade a practice of going about the streets at Christmas ove visere ne faux visage (wearing masks) and entering citizens’ houses “to play at dice therein,” and in 1417 “mumming” was specifically prohibited. In 1418 it was enacted in London “that no manner of person, of whatever estate, degree, or condition that ever he be, during this holy time of Christmas be so hardy in any way to walk by night in any manner mumming, plays, interludes, or any other disguisings with any false beards, painted masks, deformed or colored faces in any way . . . except that it is lawful for each person to be honestly merry as he can, within his own house dwelling”*5 (Riley 1868, 669). In Germany they were still trying to stop Yuletide guisers appearing. Fear of magic and witchcraft went well beyond the persecution of those who were believed to practice magic. In 1452 masks were banned again in Regensburg, having been banned previously in 1249 (Schwedt, Schwedt, and Blümke 1984, 10; Bärtsch 1998 [1933], 34). The Bavarian Tegernsee Manuscript of 1458 recorded that women led by Frau Percht approached human habitations during the Christmas period, and in 1480 the Discipuli Sermones also in south Germany condemned people who believed in the goddess “Diana, commonly known as Percht,” who wandered in a throng through the darkness. In Nuremberg in 1496 blackening or reddening faces was prohibited. Like so many official prohibitions, all of these edicts seem to have had little effect.

The ragged Yuillis Yald (Yule Horse) was mentioned by the royal bard of Scotland, William Dunbar, in the late fifteenth century. In 1543 the Bishop of Zealand in Denmark warned his flock not to observe “unholy watch night” (New Year’s Eve) because the Hvegehors, a man guising as a horse, was part of the observance (Alford 1968, 132). In 1545 in Rottweil, Germany, “ larven” (carnival masks) were prohibited. Masked performers in the Perchtenlauf and carnivals of Germany were repeatedly subject to punishment. In Bavaria, bans were enacted in 1582, 1596, and 1600. In Berchtesgaden, the spiritual home of Frau Percht, the Perchtenlauf was banned in 1601. In Riedlingen in 1745 there were prosecutions of people who wore masks. The revolution of 1848 in Swabia gave all citizens the right to wear masks again legally. The longest suppression of all was in Biberach, where guising was banned in 1599 and did not return until 1987 (Wiesinger 1980, 31). In the twenty-first century, ritual disguise still appears in many parts of Europe, not least in Santa Claus costumes (with false beards). The Perchtenlauf runs, the Krampus terrifies, straw bears jostle in the streets, the festival of fools rolls on, and in Britain pantomimes with cross-dressed main characters are put on in many city theaters around the Christmas season.

Fig. 16.2. Krampus, Austria.

THE OLD HORSE

The mummers’ horse using a real horse’s skull was significant in British country rites and ceremonies. It is still used in various mummers’ plays of the Old Oss (old horse), from whose knockabout antics comes the word horseplay, and where the horse kills a blacksmith who is then brought back to life by a doctor. In Derbyshire the old horse appears at Yuletide, sometimes alongside the Old Tup, a mummer guising as the Derby Ram. The oldest known photograph of an English mummers’ team, taken in 1870 at Winster Hall, Derbyshire, has a “horse” made from a horse’s skull. At Eckington a skull was dug up from a horse’s grave especially for the play. “It seems as if the old horse,” wrote S. O. Addy in 1907, “were intended to personify the aged and dying year. The year, like a worn-out horse, has become old and decrepit, and just as it ends, the old horse dies. The time at which the ceremony is performed, and its repetition from one house to another, indicate that it was a piece of magic intended to bring welfare to the people in the coming year.” Addy also noted that “guising was known among the old Norsemen as skin-play (skinnleikr)” (Addy 1907, 40—42; Cawte 1978, 112—18).

In 1850 a correspondent using the pen name “Pwwca” wrote to Notes and Queries: “A custom prevails in Wales of carrying about at Christmas time a horse’s skull dressed up with ribbons, and supported on a pole by a man who is concealed under a large white cloth. There is a contrivance for opening and shutting the jaws, and the figure pursues and bites everybody it can lay hold of, and does not release them except on payment of a fine. It is generally accompanied by some men dressed up in a grotesque manner, who, on reaching a house, sing some extempore verses requesting admittance, and are in turn answered by those within, until one party or the other is at a loss for a reply. The Welsh are undoubtedly a poetical people, and these verses often display a good deal of cleverness. This horse’s head is called Mari Lwyd, which I have heard translated ’grey mare’” (vol. 1 [1850], 173). A similar Twelfth Night custom on the Isle of Man was recorded by Arthur Moore in 1891:

During the supper the laare vane, or white mare, was brought in. This was a horse’s head made of wood, and so contrived that the person who had charge of it, being concealed under a white sheet, was able to snap the mouth. He went round the table snapping the horse’s mouth at the guests who finally chased him from the room, after much rough play. (Moore 1891, 104—5)

Horse-mask customs continue to this day in Mecklenburg and the Harz Mountains of Germany, as well as the Innviertel region of Austria.

In Britain and Ireland, the day after Christmas, St. Stephen’s Day, or Boxing Day saw a ritual wren hunt. The wren is a bird that according to custom was left alone except on December 26, when the local Wren Boys went out to hunt one. When they tracked down a wren among the hedges and brambles, it was killed and brought back processionally to the village tied on top of a pole bedecked with fine ribbons. In Wales some Wren Boys made wooden cages to carry the wren around. It was taken from house to house and inn to inn, where special songs about the wren were sung, with titles such as “Please to See the King” and “The Cutty Wren.” In Ireland the bodhrán was the ceremonial instrument of the Wren Boys. Killing an otherwise protected bird is an instance of reversal in the Yuletide period, which included a feast overseen by a person designated the Lord of Misrule, who permitted card playing and other forms of gambling and performance that were prohibited at other times of year. In Denmark there is a particular card game called Gnav, which was only played at Christmastime. Yule was a time of license.

TWELFTH NIGHT

The end of the festival of Yule/Christmas was Twelfth Night, the Christian festival of Epiphany. The custom of wassailing apple trees in England and Wales is observed traditionally around Twelfth Night. Wassailing began as an Anglo-Saxon drinking custom, centered on the loving cup and the wassail bowl, brimming with spiced alcoholic drink. The custom of groups of people visiting houses with a wassail bowl and singing for largesse had become established by 1600, and a rich tradition has come down to us, involving drinking, singing, dancing, guising, and processing from place to place (Cater and Cater 2013, 15—50). Wassailing was and is conducted in fruit orchards, to charm the trees to bear plenty of fruit in the coming season. There are special wassail songs. In his Hesperides (1648) Robert Herrick encouraged the wassailing of fruit trees:

Wassaile the trees, that they may beare

You many a Plum, and many a Peare;

For more or lesse fruits they will bring,

As you doe give the Wassailing.

(HERRICK1902 [1648], 251)

SPEED THE PLOUGH

Plough Monday is the Monday after Twelfth Night, when the fieldwork began again after the twelve days of Christmas. It is an ancient custom observed mainly in the eastern half of England that continues today, bringing out the plough to magically ready it for the work ahead. There are several theories about the day’s origin, assuming that it has a single origin. One theory is that it was brought to England in the ninth century by Danish settlers as Midvintersblót, the day marking the middle of the winter season twenty days after Yule. The day also commemorated the victory of the Danish army over the forces of Wessex in the year 878 that occurred “at midwinter after Twelfth Night,” which was Midvintersblót or Tiugunde Day, January 13. The Danelaw was established in that year, and eastern England was under Danish rule thereafter.

Another theory is that Plough Monday was established by the Archbishop of York in the eleventh century. But it is clear that, whatever other festivals have been attached to it, it is related to the return to work after the twelve days of Yule. There is an inscription dating from the late fourteenth century on a beam in the gallery called the Plough Rood of Cawston Church, Norfolk: “God spede the plow, And send us all corne enow, Our purpose for to mak, At crow of cok, Of the plwlete of Lygate, Be mery and glade, Wat Good ale this work mad” [God speed the plough and send us ale and corn enough, our purpose for to make at dawn at the plough light of Lygate. Be merry and glad, what good ale this work made]. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, F. Blomefield wrote: “Anciently, a light called the Plough Light was maintained by old and young persons who were husbandmen, before images in some churches, and on Plough Monday they had a feast, and went out with a plough and dancers to get money to support the Plough Light. The Reformation put out these lights, but the practice of going about with the plough, begging for money remains, and the ’money for light’ increases the income of the village alehouse” (Blomefield 1805—1810, 9, 212).

In England, Plough Monday was the traditional beginning of the New Year’s ploughing. It was marked by a procession of plough-boys and ploughmen around their local villages, dragging a plough. In nineteenth-century England, there were two parallel Plough Monday traditions, coming from regions where ploughing was done by oxen or by horses. In eastern England at Helpston, north of Peterborough, in the 1820s the peasant poet John Clare recorded that on Plough Monday the Plough Bullocks (from the oxen tradition) all blacked their faces, while only some of the Plough Witches did. The “She Witch” had his face “raddled,” a mixture of colors. In 1873 a newspaper reported what it hoped was the end of Plough Monday observance in Ramsey, which it called “this licensed system of begging and the attendant foolery of disguised villagers in the bloom of red ochre, the sickly pallor of whiting, or the orthodox demoniacal tint of lampblack” (The Peterborough Advertiser, January 18, 1873, 3). A record from Eye, to the east of Peterborough, in 1894, tells how then on Plough Monday “a large number of plough boys attired in the most grotesque manner, having faces reddened with ochre or blackened with soot, waited on those known to be in the habit of remembering the poor old ploughboy” (Peterborough and Huntingdonshire Standard, January 13, 1894, 8).

Fig. 16.3. Plough parade at Whittlesea, Cambridgeshire, England.

A correspondent to Fenland Notes & Queries in 1899 records how “the custom on Straw Bear Tuesday was for one of the confraternity of the plough to dress up with straw one of their number as a bear and call him the Straw Bear. He was then taken round the village to entertain by his frantic and clumsy gestures the good folk who on the previous day had subscribed to the rustics’ spread of beer, tobacco, and beef, at which the bear presided” (Fenland Notes & Queries IV [1899], 228). At Ramsey, Huntingdonshire, where the Straw Bear presided over the festivities, there was an element of tolerated misrule. It was the custom to settle personal scores on Plough Monday by playing practical jokes. This might involve ploughing up the garden or the front step, moving the water butt so it would flood the house when the front door was opened, taking gates off their hinges and throwing them in the nearest dyke (Marshall 1967, 200—1). At Great Sampford in Cambridgeshire around 1890 on Plough Monday the Accordion Man was accompanied by the Pickaxe Man, who used his tool to dig up boot scrapers when requested, “up with the scraper, Jack!” At West Wratting, Billy Rash told folklorist-performer Russell Wortley in 1960 that on one occasion when money was refused them, the ploughboys ploughed a furrow across the lawn of the big house in the village. In Whittlesea in Eastern England (also spelled Whittlesey), the custom was actively suppressed in 1907 by police action (Frazer and Moore Smith 1909, 202—3), though a straw bear was made on later occasions even after World War I and ran clandestinely from house to house avoiding police patrols (Gill Sennett, personal communication). The Whittlesea Straw Bear reappeared in 1980, and now in the early twenty-first century it presides over a major festival attended by thousands. Straw bears appear in various parts of Germany around the same time of year, marking the beginning of the carnival period. One from Wilflingen is shown in figure 16.4.

Fig. 16.4. Straw Bear and attendants at Wilflingen, Germany.

FEBRUARY AND THE END OF WINTER

St. Brigid’s Day and Candlemas, February 1—2 are often conflated, as they coincide with the old Celtic festival called Imbolc or Oimelc. The first is St. Brigid’s Day (Feil Brighde in Irish). Traditionally it was reckoned as the first day of spring in Ireland. On St. Brigid’s Day an effigy called the breedhogo was carried around by young people from house to house, where collections of food and money were made “in honor of Miss Biddy.” The breedhogo was an effigy made from straw in the form of a human figure. It had a head made from a ball of hay, and the figure was clad in a woman’s dress and a shawl. A straw plait called Brigid’s cross was made on St. Brigid’s day and hung up inside the house until replaced by another in the following year.

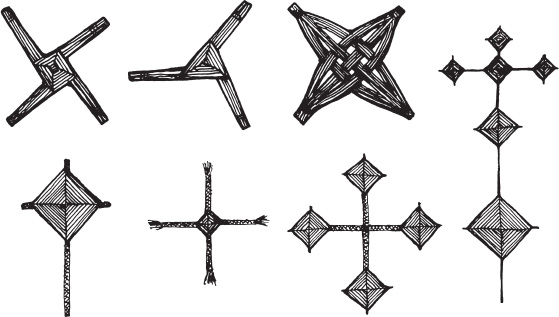

Fig. 16.5. St. Brigid’s Cross, Ireland, and related straw plaits.

Many festive days were marked by bonfires, and in Geraardsbergen, Flanders (Belgium), the Tonnekensbrand is burned to mark the end of winter and the return of the light and the growing season. At sunset a tar barrel is set alight on the summit of the Oudenberg, and surrounding villages respond to the Tonnekensbrand with local fires. The Tonnekensbrand is a fire feast that has its own ritual food, the krakeling, bread in the form of a ring, thrown to the participants by the mayor. In Swabia (south Germany), on the first Sunday after Ash Wednesday (Funkensonntag), an effigy was burned in the Funkenfeuer.

At the end of winter, the ritual of spring cleaning the house takes place, usually in early March, and March 1 was the favored day in parts of England. The house had to be swept thoroughly before a threshold pattern was chalked on the front doorstep. In Cambridgeshire it was called Foe-ing Out Day. The belief was that if this day was not kept up, the household would suffer from an infestation of fleas for the following year.

Fig. 16.6. Foe-ing Out Day threshold pattern in chalk (Cambridge Box), South Cambridgeshire, England.

CARNIVAL AND EASTER

The beginning of the Christian fast called Lent (Shrovetide) was marked by the carnival (farewell to meat), culminating in Shrove Tuesday (Fastnacht, Fasnet, Fasching, or Mardi Gras). This was a time of festivity and license, characterized by parades of masked people guising as various local mythic characters and beasts. In Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, the tradition of wearing carved wooden masks continues. As with guising customs at other times of year, current performance has come through centuries of intermittent persecutions. In some places the ceremonial masks are kept hidden away for most of the year, to be brought out at the right time and ceremonially awakened. After the events they are carefully put back to sleep until the next year.

A man of straw can be just an empty straw effigy or may actually have a man inside, as the straw bears do. It is unnerving to see a seemingly lifeless straw man suddenly come to life. Straw men with wooden masks perform in central Europe in Slovenia, Slovakia, Serbia, and Croatia. Straw Boys come out in Ireland and attend weddings, at one time whether or not they were invited. Unmanned straw men called Jack O’Lent were burned at mid-Lent in England. Jack O’Lent was beaten, kicked, shot at, or burned. In Cornwall he was identified with Judas Iscariot (Wright and Lones 1936, I 38). In Liverpool straw effigies of Judas were burned on Good Friday.

Fig. 16.7. Masked performers on Shrove Tuesday at Rottweil-am-Neckar, Germany.

The German equivalent of Jack O’Lent appears on windowsills in south Germany now during the period of Fastnacht (Shrovetide). Breughel’s painting The Battle of Carnival and Lent (1559) has a clothed stuffed straw figure sitting on just such a ledge. In Germany this straw man is alternatively called the Todpuppe: a symbol of death appearing in the ceremony of Todaustragen, “driving out death” (Flaherty 1992, 40—55). In his 1863 book Das Festliche Jahr, Freiherr von Rheinsberg-Düringsfeld described the effigy of Death being made of old straw with sticks as arms and legs, clad in old clothing with a face of white linen. Young people danced hand in hand around it, singing and jeering, either dragging the effigy to a bridge and throwing it off into the water, or taking it to a cliff and throwing it over.

In 1880 William Bottrell wrote of the practice in Cornwall, western England, “In the spring, people visit a ’Pellar’ (conjuror) as soon as there is ’twelve hours’ sun,’ to have ’their protection renewed,’ that is, to be provided with charms; and the wise man’s good offices to ward off, for the ensuing year, all evil influences of beings who work in darkness.” The reason assigned for observing this particular time is that “when the sun is come back the Pellar has more power to good [do good]” (Bottrell 1880, 187). Easter is the festival of the vernal equinox full moon personified by Ostara (Eostre to the Anglo-Saxons), the Germanic goddess of springtime, which was absorbed by the church as its main festival but retained the traditional symbolic eggs and related customs from European ancestral religion. Because hens begin to lay eggs only when days get longer than nights at the vernal equinox, eggs are symbols of springtime. It is traditional to paint them red or with complex patterns. The oldest extant spring “Easter” egg known was found at Wolin, in Poland. Covered with marbled patterns, it dates from the tenth century CE. In parts of Germany, springs and wells are decked with thousands of colored eggshells. The Estonian runic calendars marked “ploughing day,” April 14, with a tree with upward-pointing branches. October 14 was marked by a tree with drooping branches. In Britain and Scandinavia this day marked the commencement of the summer half of the year.

Fig. 16.8. Easter eggs bedecking a spring at St. Marien, Germany.

MAY DAY

In Britain the month is known as the Merry Month of May. Sir Thomas Malory’s Arthurian epic Le Morte D’Arthur (1470s) tells of Queen Gwynevere informing her knights that on May Day she would go a-maying and ordering them all to be well horsed and dressed in green. Green is the ritual color of the Merry Month of May. In many parts of Britain and Ireland, a May bush (hawthorn, Crataegus monogyna) was cut on the previous day and stuck in the ground in front of the house. An Irish tradition decorated the May bush with eggshells that had been saved up since Easter Sunday, along with ribbons, wildflowers, and candles. On May Night the candles were lit, and people danced around the May bush. The rite was said to be in honor of the Virgin Mary, to whom the month of May was dedicated. May Day marks the beginning of the summer Morris dancing season in England.

Fig. 16.9. Morris dancing at Oxford, England, on May Day morning.

The iconic image of May Day is the maypole, a widespread custom across northern Europe. A German example is illustrated in figure 16.10.

Fig. 16.10. Maypole, Wenneden, Germany.

In Wales, May Day is Calan Mai, marking the beginning of the summer half of the year, as its former name, Calan Haf, the calends of summer, denotes. The earliest literary reference to a maypole in Wales is in a poem by Gruffydd ab Adda ap Dafydd, who died around 1344. The birch maypole was known as y gangen haf (The Summer Branch), and some were painted in various colors. In 1852 the Welsh bard Nefydd (William Roberts) noted that dawns y fedwen (the Dance of the Birch; i.e., Morris dancing) at maypoles was well known all over Wales. Nefydd described the ritual preparation of the pole. First, the leader of the dance would come and place his circle of ribbon about the pole, and each in his turn after, until the maypole was covered in ribbons. Then the pole was raised into position and the dance begun; each took his place in the dance according to the personal piece of ribbon placed upon the maypole (Owen 1987, 102). In the borderlands of England and Wales, it was traditional to cut a birch tree on May morning and set it up, bedecked with white and red rags or ribbons, next to the door of a stable. This maypole was left up for the whole year and taken down only on the next May Day, when a new one was set up. A birch set up in May prevented malicious sprites from riding horses at night and tangling up their tails and manes into “witches’ knots.” In the borderlands of England and Wales, crosses of wittan (rowan) and birch, tied with red thread, were set above the cottage door, on pigsties, and in garden seedbeds. On the Isle of Man they used rowan twigs alone, broken, not cut from the tree, tied with wool taken directly from a sheep’s back, making the Crosh Keirn.

Là Beltain (May Day) in the highlands of Scotland was observed with bonfires. In the Scottish highlands in the eighteenth century, Beltane or Baaltein, the May Day festival, “was yet in strict observance.” On May Day people cut a square trench in the turf, leaving a square of grass in the middle. A Beltane cake was baked upon it “with scrupulous attention to certain rites and forms.” Then it was broken up, and the fragments, “formally dedicated to birds or beasts of prey that they, or rather the being whose agents they were, might spare the flocks and herds” (Scott 1885, 3). The ritual prayer, “This I give to Thee, preserve my [horses, cattle, etc.]” was recited as the fragments of oatcake were thrown over the shoulder. Fires were kindled upon high places in pairs and all the cattle of the district driven between them to protect them until the next Là Beltain. All house fires were put out and rekindled by fire brought from the sacred fire. Writing in the first half of the nineteenth century, Sir Walter Scott noted “remains of these superstitions might be traced till past the middle of the last century, though fast becoming obsolete, or passing into mere popular customs of the country, which the peasantry observe without thinking of their origin” (Scott 1885, 3).

In Wales, May Eve is one of the teir nos ysbrydion, the “three spirit nights” occurring each year. Divination traditionally took place on May Eve during the Swper nos Glanmai, the ceremonial May Eve supper, where future lovers could be called up, “though a hundred miles off.” A coelcerth (ritual fire) was made for Calan Mai. It was prepared by nine men who first removed all metal from their persons. Then they collected sticks from nine kinds of trees, and took them to the place where the fire was to be. A circle was cut in the turf and the sticks arranged crosswise. It was kindled by friction with two pieces of oak. Two fires close to one another were made so that livestock could be driven between them to give them magical protection against diseases. A calf or sheep would be thrown in the fire whenever there was disease in the herds. This is the tradition of the needfire, which was often conducted in extreme conditions, such as famine and pestilence, as a magical attempt to bring the crisis to an end. Ashes from the coelcerth were kept for magical purposes (Owen 1987, 97—98). Until the nineteenth century, igniting gunpowder and firing guns in the air was part of May Day custom in some English cities with strong civic traditions, including London, Norwich, and Nottingham. Contemporary Pagans keep up the day whenever possible with a Beltane fire.

MIDSUMMER AND HARVEST

Throughout northern Europe there are customs of burning bonfires and fire wheels at midsummer. The summer solstice, June 21, was also celebrated with the erection of poles (inter alia in Wales, Sweden, and Lithuania) and lighting fires. In Wales, birch poles were raised on two days in the year, May Day and St. John’s Day. The latter was y fedwen haf, the Summer Birch. Magically, the Eve of St. John is one of the Welsh teir nos ysbrydion, when spirits can be more readily contacted. St. John’s Day (June 24) is a former midsummer’s day, calendar changes having made it out of kilter with the solstice. It is the day of the Johannesfeuer bonfire. Lammas, August 1, was the Celtic Lá Lúnasa, celebrating the god Lugus, called by contemporary Pagans by its Gaelic name: Lunassadh. It is the “loaf-mass,” the festival of the grain harvest, when the first loaf of the new harvest was made and presented to the deity.

NOVEMBER, YEAR’S END

The old Celtic Samhain (Hallowe’en) in its traditional, precommercialized form signified the end of harvest, with slaughter of all livestock that could not be kept through the winter. The day marked the end of the summer half of the year and the beginning of winter. It was celebrated with bonfires and the blowing of horns (Owen 1987, 124). The ancestral dead were remembered at this time with festivals such as the Celtic Lá Samhna and Nos Galan gaeaf and the Lithuanian Vėlinės. Nos Galan gaeaf, “the eve of the calends of winter,” October 31, is Allhallows’ Eve or Hallowe’en. Calan gaeaf, November 1, was the old Celtic New Year. It was one of the teir nos ysbrydion (“three spirit nights”) in Wales, a time when wandering ghosts and demonic entities walked abroad. They included the ladi wen (white lady) and hwch ddu gwta, the terrifying tailless black sow (Owen 1987, 123). The Welsh name for November, mis Tachwedd, denotes slaughtering, and in Anglo-Saxon England, November was Blót-mónaþ, “Sacrifice Month,” when the farmers who were slaughtering farm animals that could not be overwintered dedicated them as sacrifices to the gods. Excavators of the Northumbrian Pagan temple site at Yeavering discovered a large pile of the bones and skulls of oxen inside the east door of the temple. Next to the temple was a smaller building, probably a cookhouse. The animals killed and dedicated to the gods were served up in the royal hall nearby.

In Ireland, well into the twentieth century, animals were sacrificed to St. Martin on Martinmas, November 11. In 1887 Lady Wilde noted, “There is an old superstition still observed by the people, that blood must be spilt on St. Martin’s Day; so a goose is killed, or a black cock, and the blood is sprinkled over the floor and on the threshold. And some of the flesh is given to the first beggar that comes by, in the name and in honor of St. Martin” (Wilde 1887, II, 131). In the Aran Isles the sacrificial blood was poured or sprinkled on the ground, along the doorposts, and both inside and outside the threshold, and at the four corners of each room in the house. The blood was from a sacrificed goose or rooster, but if it was not possible to get one, “people have been known to cut their finger in order to draw blood, and let it fall upon the earth. In some places it was the custom for the master of the house to draw a cross on the arm of each member of the family and mark it out in blood. This was a very sacred sign, which no fairy or evil spirit, were they ever so strong, could overcome; and whoever was signed with the blood was safe” (Wilde 1887, II, 131—32).

Another Martinmas observance in Ireland was “a singular superstition forbidding work of a certain kind to be done on St. Martin’s Day. . . . No woman should spin on that day; no miller should grind his corn, and no wheel should be turned. And this custom was long held sacred, and is still observed in the Western Islands” (Wilde 1887, II, 133).

Postscript

![]()

Tradition develops, it does not stand still. It is not an unchanging, rigid performance. It is a historical accident that certain customary rites, ceremonies, and performances have continued for a long time at certain places when similar or identical practices have ceased to be performed in others. In recent years, where the interest in vernacular performance has increased, new events have emerged. Apart from the long-standing assembly at Stonehenge at Midsummer, the Pagan community has established parades and other events, particularly in celebration of Beltane (May Day). These events draw upon traditional elements such as Jack-in-the-Green and May songs old and new. The older and newer events have one thing in common: they are keeping up the day. A particular day in the year is recognized and celebrated by a public performance, whether it be a sacred day such as Beltane or Fastnacht; a customary day such as Boxing Day and Plough Monday; or a day that has been designated by a modern interest group, for instance Apple Day. With everyday magic as well as customs, people who are alive now are performing their own interpretations of a tradition that is authentic, not because we are doing it by the book, but because we are doing it. Done properly, with respect, and on the right day, the magic is still implicit in the performance.